Last week there were several bug reports [1]

[2]

[3]

about how Chrome (the web browser), even in its fully-open-source Chromium

incarnation, downloads

a closed-source, binary extension from Google’s servers and installs it,

without telling you it has done this, and moreover this extension

appears to listen to your computer’s microphone all the time,

again without telling you about it. This got picked up by the trade

press [4] [5]

[6]

and we rapidly had a full-on Internet panic going.

If you dig into the bug reports and/or the open source part of the

code involved, which I have done, it turns out that what Chrome is doing

is not nearly as bad as it looks. It does download a closed-source

binary extension from Google, install it, and hide it from you in the

list of installed extensions (technically there are two hidden

extensions involved, only one of which is closed-source, but that’s only

a detail of how it’s all put together). However, it does not

activate this extension unless you turn on the voice

search

checkbox in the settings panel, and this checkbox has always

(as far as I can tell) been off by default. The extension is

labeled, accurately, as having the ability to listen to your

computer’s microphone all the time, but of course it does not get to do

this until it is activated.

As best anyone can tell without access to the source, what the

closed-source extension actually does when it’s activated is

monitor your microphone for the code phrase OK Google.

When it

detects this phrase it transmits the next few words spoken to Google’s

servers, which convert it to text and conduct a search for the phrase.

This is exactly how one would expect a voice search

feature to

behave. In particular, a voice-activated feature intrinsically has to

listen to sound all the time, otherwise how could it know that you have

spoken the magic words? And it makes sense to do the magic word

detection with code running on the local computer, strictly as a matter

of efficiency. There is even a non-bogus business reason why the

detector is closed source; speech recognition is still in the land where

tiny improvements lead to measurable competitive advantage.

So: this feature is not actually a massive privacy violation. However, Google could and should have put more care into making this not appear to be a massive privacy violation. They wouldn’t have had mud thrown at them by the trade press about it, and the general public wouldn’t have had to worry about it. Everyone wins. I will now dissect exactly what was done wrong and how it could have been done better.

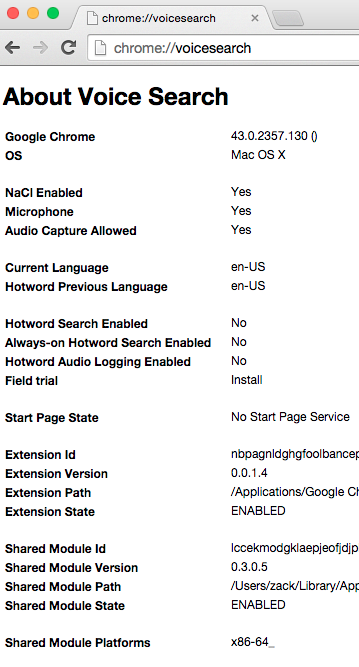

It was a diagnostic report, intended for use by developers

of the feature, that gave people the impression the extension

was listening to the microphone all the time. Below is a screen shot of

this diagnostic report (click for full width). You can see it on your

own copy of Chrome by typing chrome://voicesearch into the

URL bar; details will probably differ a little (especially if you’re not

using a Mac).

Google’s first mistake was not having anyone check this over for what

it sounds like it means to someone who isn’t familiar with the

code. It is very well known that when faced with a display like this,

people who aren’t familiar with the code will pick out whatever bits

they think they understand and ignore everything else, even if that

means they completely misunderstand it. [7]

In this case, people see Microphone: Yes

and Audio Capture

Allowed: Yes

and maybe also Extension State: ENABLED

and

assume that this means the extension is actively listening right now.

(What the developers know it means is this computer has a microphone,

the extension could listen to it if it had been activated, and

it’s connected itself to the checkbox in the preferences so it

can be activated.

And it’s hard for them to realize that

anyone could think it would mean something else.)

They didn’t have anyone check it because they thought, well, who’s going to look at this who isn’t a developer? Thing is, it only takes one person to look at it, decide it looks hinky, mention it online, and now you have a media circus on your hands. Obscurity is no excuse for not doing a UX review.

Now, mistake number two becomes evident when you consider what this screen ought to say in order not to scare people who haven’t turned the feature on (and maybe this is the first they’ve heard of it even): something like

Voice Search is inactive.

(A couple of sentences about what Voice Search is and why you might want it.) To activate Voice Search, go to the preferences screen and check the box.

It would also be okay to have a duplicate checkbox right there on

this screen, and to have all the same debugging information show up

after you check the box. But wait—how do developers diagnose

problems with downloading the extension, which happens before the box

has been checked? And that’s mistake number two. The extension

should not be downloaded until the box is checked. I am not aware

of any technical reason why that couldn’t have been the way it worked in

the first place, and it would go a long way to reassure people that this

closed-source extension can’t listen to them unless they want it to.

Note that even if the extension were open source it might still be a

live question whether it does anything hinky. There’s an excellent

chance that it’s a generic machine recognition algorithm that’s been

trained to detect OK Google

, which training appears in the code

as a big lump of meaningless numbers—and there’s no way to know whether

those numbers train it to detect anything besides OK

Google.

Maybe if you start talking about bombs the computer just

quietly starts recording…

Mistake number three, finally, is something they got half-right. This is not a core browser feature. Indeed, it’s hard for me to imagine any situation where I would want this feature on a desktop computer. Hands-free operation of a mobile device, sure, but if my hands are already on a keyboard, that’s faster and less bothersome for other people in the room. So, Google implemented this frill as a browser extension—but then they didn’t expose that in the user interface. It should be an extension, and it should be visible as such. Then it needn’t take up space in the core preferences screen, even. If people want it they can get it from the Chrome extension repository like any other extension. And that would give Google valuable data on how many people actually use this feature and whether it’s worth continuing to develop.