Readers of this blog will probably already know that, up till the

middle of last year, it was possible to sniff

browsing history by clever tricks involving CSS, JavaScript, and the

venerable tradition of drawing hyperlinks to already-visited URLs in

purple instead of blue. Last year, though, David Baron came up with a defense

against history sniffing which has now been adopted by every major

browser except Opera. One fewer thing to worry about when visiting the

internets, hooray? Not so fast.

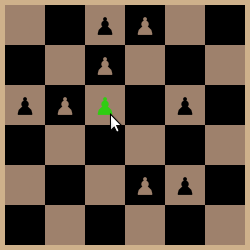

Imagine for a moment that the next time you visited an unfamiliar website and you wanted to leave a comment without creating an account, instead of one of those illegibly distorted codes that you have to type back in, you saw this:

Please click on all the chess pawns.

As you click on the pawns, they turn green. Nifty, innit? Much easier than an illegibly distorted code. Also easy for a spambot equipped with image processing software, but it turns out the distorted codes are not that hard for spambots anymore either and probably no one’s written the necessary image processing code for this one yet. Possibly also easier on people with poor eyesight, and there could still be a link to an audio challenge for people with no eyesight.

… What’s this got to do with history sniffing? That chessboard isn’t

really a CAPTCHA. All the squares have pawns on them. But each

one is a hyperlink, and the pawns linked to sites you haven’t visited

are being drawn in the same color as the square, so they’re invisible.

You only click on the pawns you can see, of course, and so you reveal to

the site which of those URLs you have visited. A little technical

cleverness is required—the pawns have to be Unicode dingbats, not

images; all the normal interactive behavior of hyperlinks has to be

suppressed; etcetera—but nothing too difficult. I and three other

researchers with CMU

Silicon Valley’s Web Security Group have tested this and a few other

such fake CAPTCHAs on 300 people. We found them to be practical,

although you have to be careful not to make the task too hard; for

details please see our

paper (to be presented at the IEEE Symposium on

Security and Privacy, aka Oakland 2011

).

An attacker obviously can’t use an interactive sniffing

attack

like this one to find out which sites out of the entire Alexa 10K your

victim has visited—nobody’s going to work through that many

chessboards—and for the same reason, deanonymization

attacks that require the attacker to probe hundreds of thousands of URLs

are out of reach. However, an attacker could reasonably probe a couple

hundred URLs with an interactive attack, and according to Dongseok Jang’s study

of actual history sniffing (paper),

that’s about how many URLs real attackers want to sniff. It seems that

the main thing real attackers want to know about your browsing history

is which of their competitors you patronize, and that’s never going to

need more than a few dozen URLs.

On the other hand, CAPTCHAs are such a hassle for users that they cause 10% to 33% attrition in conversion rates. And users don’t expect to see them on every visit to a site—just the first, usually, or each time they submit an anonymous comment. Even websites that were sniffing history when it was possible to do so automatically, and want to keep doing it, may consider that too high a price. But we can imagine similar attacks on higher-value information, where even a tiny success rate would be worth it. For instance, a malicious site could ask you to type a string of gibberish to continue—which happens to be your Amazon Web Services secret access key, IFRAMEd in from their management console. Amazon has taken steps to make this precise scenario difficult, but I’m not prepared to swear that it’s impossible, and other cloud services providers may have been less cautious.

Going forward, we also need to think carefully about how new

web-platform capabilities might enable attackers to make similar

end-runs around the browser’s security policies. In the aforementioned

research project, we were also able to sniff history without

user interaction by using a webcam to detect the color of the light

reflecting off the user’s face; even with our remarkably crude

image processing code this worked great as long as the user held still.

It’s not terribly practical, because the user has to grant access to

their webcam, and it involves putting an annoying

flashing box on the screen, but it demonstrates the problem. We are

particularly concerned about WebGL

right now, since its shader programs

can perform arbitrary

computations and have access to cross-domain content that page

JavaScript cannot see; there may well be a way for them to communicate

back to page JavaScript that avoids the <canvas>

element’s information leakage rules. Right now it’s not possible to

put the rendering of a web page into a GL texture, so this couldn’t be

used to snoop on browsing history, but there’s legitimate reasons to

want to do that, so it might become possible in the future.